James Montier is an investment banker with Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein (a European bank) who often writes sober, fiscally conservative reports urging people to invest their money in a sober, fiscally conservative manner. His report titled Part Man, Part Monkey [PDF version | web version] has a pretty good “top ten list” for avoid financial pitfalls. The Gambler’s Fallacy [PDF version | web version] takes a look at a common misperception that plagues both gamblers and investors alike.

The paper of Montier’s that really caught my attention is titled If It makes You Happy [189K PDF], one in which he doesn’t talk about investing at all — at least not in the way we think of it. It’s about a pet topic of mine, something I might go so far as to call a hobby: happiness.

Why Be Happy?

The first question he asks in his essay is “Why be happy?” Here’s his list of answers, which are listed below and are based on “based on careful scientific studies (rather than cheap self help books!)”. (He also directs the reader to Dr. Sonja Lyubomirsky at University of Califonia Riverside, who has devoted the majority of her reasearch career to studying human happiness.)

- Social rewards

- Higher odds of marriage

- Lower odds on divorce

- More friends

- Stronger social support

- Richer social interactions

- Superior work outcomes

- Greater creativity

- Increased productivity

- Higher quality of work

- Higher income

- More activity, more energy

- Personal benefits

- Bolstered immune system

- Greater longevity

- Greater self control and coping abilities

I’m certain you can come up with your own list of reasons that best suits you.

What Makes Us Happy?

I’m posing this question in the broadest sense — what are the general categories of factors that contribute to our happiness? According to a paper by Sheldon, Lyubomirsky and Schkade titled Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Change [PDF version | web version], it boils down to three general factors:

- A set point, probably based on your brain chemistry and determined by your genes. Sheldon, Lyubomirsky and Schkade write that this set point “likely reflects immutable interpersonal, temperamental and affective personality traits, such as extraversion, arousability and negative affectivity, that are rooted in neurobiology, …are highly heritable… and change little over the lifespan.” Translation: there’s not much you can really do about this one.

- Circumstances. Simply put, a married, well-paid, secure, healthy person with a rich religious or spiritual life and a strong support network of friends and family and meaningful work is more likely to be happy than a struggling recently-dumped unemployed pariah on oxycontin whose life philosophy is nihilism. Some circumstances are easier to change than others. For example, switching careers is one thing; getting the hell out of North Korea is something else entirely.

- Intentional activity. These are actions and practices you choose to undertake. Of the three general factors that contribute to happiness, this is the on you can affect the most.

Here’s how the three factors listed above break down, according to the research. The stuff in red are my annotations.

Circumstances

Note that circumstances plays the smallest role. That’s due to something called hedonic adaptation, a ten-dollar term that has the same essence as the saying “time heals all wounds”. We have an ability to adjust to changes to our lives, good or bad, and assimilate them so that they become “the new normal”. We get used to getting a job with a bigger income, the initial flush of a new romance eventually fades (either into something longer-term or it fizzles out) and the dream place you moved to will sooner or later just be part of your everyday life. Lest you think that hedonic adaptation is a bad thing, it also blunts the sting of a death in the family over time and lets you get over the many defeats that life will hand you.

The research shows that money does not necessarily equal happiness. In fact, a survey of over 7000 students across 41 countries found that those who valued love more than money reported greater satisfaction with their lives than those who valued money over love. Here’s the chart of the results:

(Don’t get me wrong. Viewed as a means to certain kinds of freedom, money can assist happiness. It’s just not the whole ball o’ wax.)

The “Set Point”

I’ve already mentioned that there’s not much you can do about the set point of happiness that got installed in you at the factory. Barring some kind of gene therapy for happiness, you can either languish in Philip Larkin’s poem:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

…or you can concentrate on the factor that you can best control: intentional activity.

Intentional Activity

As any biologist will tell you, genes plus environment equals “this is your life”. Intentional activity is simply the set of things you do and is the best way for you to influence you environment. It’s also the factor that can account for 40% of your happiness.

Some of my friends are what I like to call “misery-seeking missiles” because their approach to life — and hence their actions and choices — tends to make them unhappy. I should send them this top ten list from Montier’s report, which explains what you can do to be happier:

- Don’t equate happiness with money. People adapt to income shifts

relatively quickly, the long lasting benefits are essentially zero.

- Exercise regularly. Regular exercise is an effective cure for mild depression

and anxiety. It also stimulates more energy, and is good for the mind and

body.

- Have sex (preferably with someone you love). Need I say more?

- Devote time and effort to close relationships. Confiding and discussing

problems and issues is good for happiness, so work on these relationships.

- Pause for reflection, meditate on the good things in life. Focusing on the

good aspects of life helps to prevent hedonic adaptation.

- Seek work that engages your skills, look to enjoy your job. Doing well at

work creates happiness, and the easiest way of doing well at work, is doing a

job you enjoy.

- Give your body the sleep it needs. Too many people have a sleep deficit,

resulting in fatigue, gloomy moods and lack of concentration.

- Don’t pursue happiness for its own sake, enjoy the moment. Because

people don’t understand what makes them happy, pursuing happiness can be

self-defeating. Additionally, if people start to aim for happiness they are doing

activities for happiness’s sake rather than actually enjoying the activity itself.

- Take control of your life, set yourself achievable goals. People are

happiest when they achieve their aims, so set yourself goals which stretch

you, but are achievable.

- Remember to follow rules 1-9. Following these guidelines sounds easy, but

actually requires willpower and effort.

If you’d like to read more, I’ve enclosed Montier’s paper for your perusal. Read it, and get working on being happy!

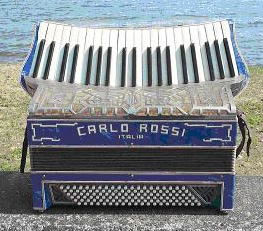

Caroline Hunt from Avoch, Black Isle, Scotland has spent the last 12 years collecting photos of accordions made between 1850 and 1960 for her upcoming reference book on the Greatest Instrument Ever. In the process, she’s also managed to collect 300 accordions, all of which are on display at Grantown on Spey Museum until Sunday.

Caroline Hunt from Avoch, Black Isle, Scotland has spent the last 12 years collecting photos of accordions made between 1850 and 1960 for her upcoming reference book on the Greatest Instrument Ever. In the process, she’s also managed to collect 300 accordions, all of which are on display at Grantown on Spey Museum until Sunday.