I pointed a friend of mine who works in finance — I’ll call him “Senor Gumbo” — to my earlier post in which I explained “longing” and “shorting” to see if I’d explained it properly. He said that I’d nailed it, but he also said that I should more clearly explain what happens if you bet the wrong way when longing or shorting.

At first I thought that I didn’t need to do that, since that should be obvious. After thinking about it some more, I was reminded of something my buddy George likes to say every now and again: “there’s power in stating the obvious”.

So now, via the magic of dry-erase markers and boards, I present: Winning and Losing When Longing and Shorting.

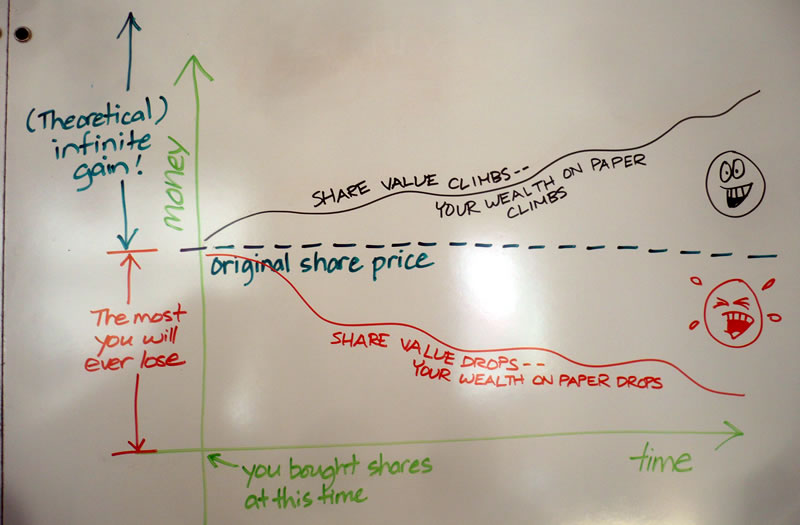

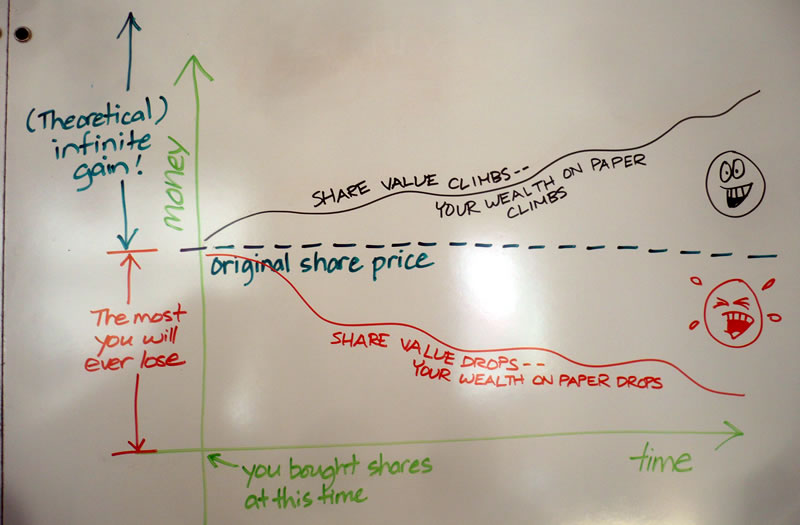

Winning and Losing When Longing

A quick recap: longing is the intutively obvious way to play the stock market. You buy shares that you believe will increase in value over time and eventually sell them for more than you paid for them.

The dry-erase board chart below shows two generalized outcomes of longing:

- You bet correctly and their price went up (the black line on the graph)

- You bet incorrectly and their price went down (the red line on the graph)

If you bet correctly, the trend in your stock price will look something like the black line, which shows its value generally increasing over time (in order to keep things simple, neither trend shows wild fluctuations). The dashed line in the graph represents the price you paid for the shares, the black line shows the price of shares over time, and the money you gained at any point in time is represented by the distance between between those two lines.

In theory, the price of the shares can go up forever, which means that when longing your profits can go up forever (in theory; if you know of a stock like this that exists in reality, could you kindly email me once you’re done reading?). There is no limit to how much profit a stock can provide…in theory.

If you bet incorrectly, the trend in your stock price will look something like the red line. Once again, the dashed line in the graph represents the price you paid for the shares. The red line shows the price of shares over time. The money you lose at any point in time is represented by the distance between those two lines.

There is a practical maximum to the money you lose when longing. Since the lowest possible stock value is zero — that’s when the company goes under — the most you can lose when longing a stock is what you initially paid for the shares.

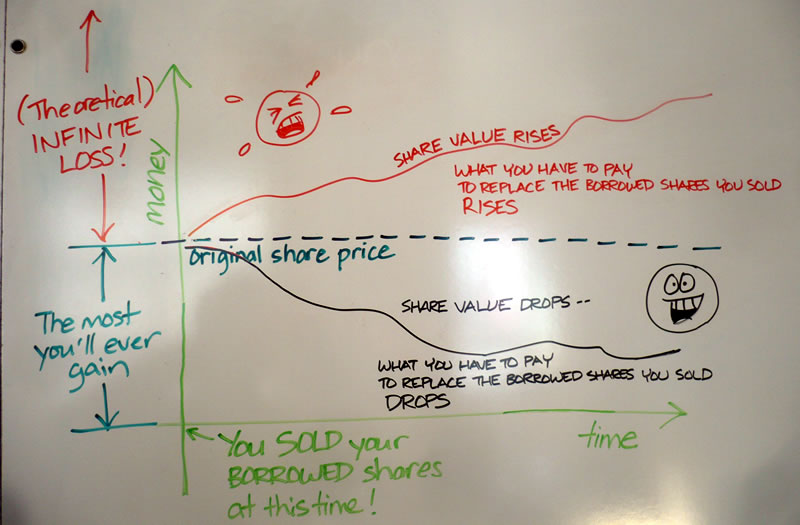

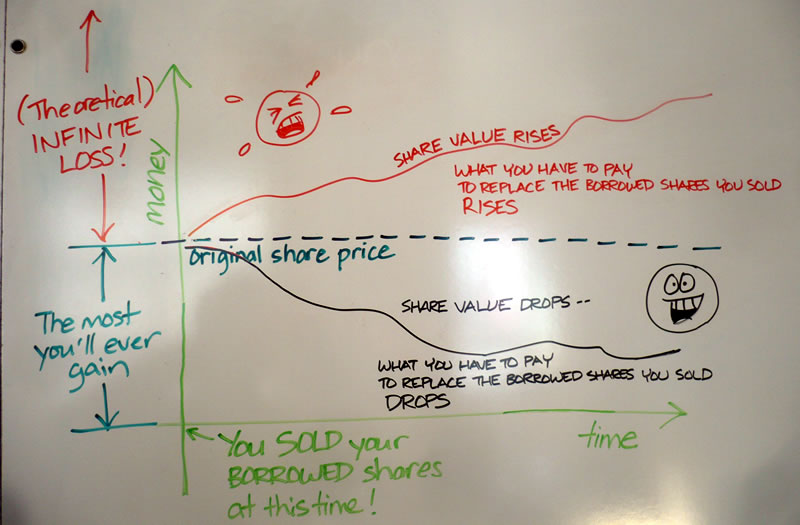

Winning and Losing When Shorting

As I mentioned in that earlier post, shorting seems like something from the Bizarro World, where everything is backwards. When you short a stock, you’re trying to make money by betting that its value will drop. You do this by borrowing shares in a stock from a broker and then immediately selling them. When their price drops, you buy an equivalent number of shares in the same stock and give them to the broker. You keep the difference between the price you sold the borrowed shares for and what you paid to buy the replacement shares.

The dry-erase board chart below shows two generalized outcomes of shorting:

- You bet correctly and their price went down (the black line on the graph)

- You bet incorrectly and their price went up (the red line on the graph)

Again, the black line on the graph shows the stock price trend if things are going your way; the difference is that when shorting, a drop in share prices is good. It means it costs less to “buy back” the shares you sold than it did to sell them, which means you make a profit.

Unlike longing, there is a practical maximum to how much money you can make by shorting. You hit this maximum when the share price drops to zero, meaning that the company has gone under, which in turn means you don’t have to return the stock to the broker. You keep all the money you made when you sold those borrowed shares (minus fees, including what the broker charged you for borrowing those shares, of course).

The red line shows the stock price trend if things are not going your way. It’s bad when the stock price is higher than when you sold those borrowed shares; it means that the cost of replacing them is higher than what you made when you sold them, meaning that you owe the broker money.

Here’s where the theoretical infinity of the stock value will nail you: if there is no (theoretical) limit to the price of shares, there is no (theoretical) limit to what you can lose by shorting. With longing, you can’t lose more on a share than what you initially paid for it; with shorting, you can lose way more than the share’s original value.

I hope that makes things clearer. If you’ve got questions or something to say, please feel free to put them in the comments. If I can’t answer your questions, I can always ask Senor Gumbo.