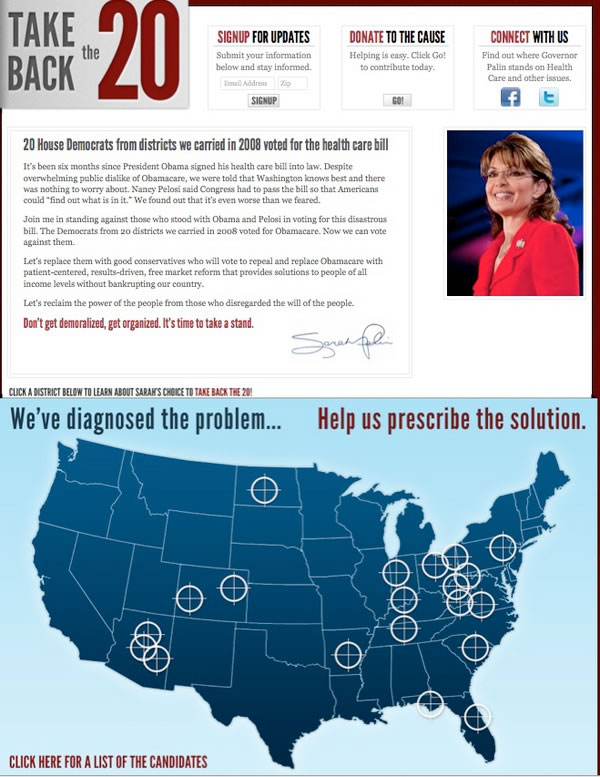

There’s an article that’s making the rounds in techie and entrepreneurial circles in Accordion City: it’s The Don’t Be an Asshole Rule, written by Aron Solomon. The asshole to which he’s referring in the article is Uber, the online service in the business of connecting people who want rides with taxis, limos, or enterprising people who’d like to make some extra money driving people around. During Monday’s storm, which left large areas of the city flooded or without power, the roads gridlocked, and thousands of people stranded in the rain, Uber increased the price of their private car service to nearly twice the normal rate. Uber calls it “surge pricing”, but many people called it “price gouging”. Kerry Morrison was one of the first people I saw tweeting his displeasure over surge pricing:

If you look at Uber Toronto’s Twitter feed at the time of this writing (almost noon on Wednesday, June 10th), they’re still in full PR defensive mode, explaining their decision to use surge pricing on their private car service, stating that it never applied to taxis, and stating that the increased prices, some of which would be passed along to drivers, was needed to provide an incentive to private car owners to go out onto gridlocked, unlit, and possibly flooded streets without traffic lights.

This isn’t Uber’s first controversy over surge pricing. They doubled the price of private car service in the New York City / New Jersey area during Hurricane Sandy, which was also met with calls of price gouging. The PR backlash was bad enough that they had to reduce their rates back to standard, but in order to keep drivers happy, continued to pay them at double their going rate. This damage control is reported to have cost them $100,000 a day, and it looks as though they haven’t learned their lesson, in spite of the tuition fee.

Uber isn’t the first company with a self-inflicted wound over variable pricing. In fact, there’s a lesson that Coca-Cola learned at the turn of the millennium that’s often taught in business school.

In 1999, Douglas Ivester was the CEO of Coca-Cola. Hailed as a brilliant guy, hand-picked and groomed by his predecessor Robert Goizueta and so data-driven that Fortune wrote “Ivester may give us a glimpse of the 21st-century CEO, who marshals data and manages people in a way no pre-Information Age executive ever did or could,” he should’ve had a successful run as leader of the world’s number one beverage company. Instead, his tenure as CEO was short, with Coke’s board of directors — one of whom was Warren Buffett — asking him to resign a mere two years after he got the job.

While Ivester had a talent for business and number-crunching, he lacked the ability to handle the sensibilities of people, whether they were in the company or Coke’s customers. He snubbed key people within the organization, micromanaged, and alienated the bottlers, who in the soft drink industry, are key allies. He also did a terrible job with customers, most notably responding way too slowly when bad batches of Coke made people in Belgium ill, and attempting to introduce variable pricing at Coke vending machines.

Illustration by Liz Meyer for a Time magazine article.

The idea behind variable pricing is a simple one: you adjust the price of a good or service that you’re selling based on some kind of factor, such as demand, where the product is being sold, the time of year, and so on. Ivester wanted to do was rig Coke vending machines so that the price would vary depending on the outside temperature that day: on hot days, a can or bottle of Coke would cost more, on cold days, they’d cost less.

The New York Times explained the logic behind Ivester’s thinking back in 1999, and it’s the sort of thing that you’d find in an Economics 101 textbook, in the section that introduces demand curves. Your desire for a nice cold Coke during a big championship game on a hot summer day would be much higher than usual, and presumably, you’d get more of what economists call utility from a cold drink on such a day. So it’s worth more, isn’t it? Ivester, ever the number-cruncher thought so, saying — and I’m using an actual quote here:

“So, it is fair that it should be more expensive. The machine will simply make this process automatic.”

What makes perfect sense in the overly-simplified, assumption-heavy world of Economics 101 doesn’t always make an equivalent amount of sense in the real world, and the variable-pricing vending machines came off as a form of high-tech price gouging. It didn’t make Coke look like a rational actor simply collecting a fair profit from increased utility for a product sold; it them look like sugar-water-shilling douchenozzles.

People accept variable pricing in a number of situations. We accept that airline ticket prices change daily, with the price climbing as the date of the flight nears. We also accept that airline tickets are more expensive during peak travel times. We accept that gas prices fluctuate, sometimes a number of times during the day, and the most certainly climb during weekends and holidays. We accept that housing prices climb as the supply of houses diminishes.

In all of these cases, we’ve accepted these differences in price as reasonable, partly because we can see the reasons behind the pricing are complex, and partly because the price changes are predictable. We know that flights will be more expensive around Christmas, and we know that the demand for them will be high.

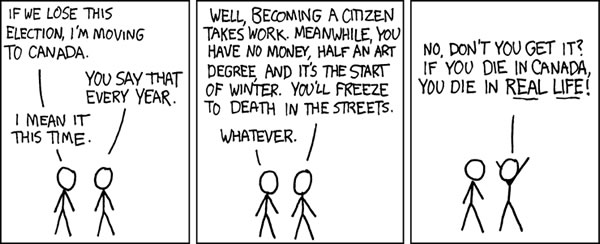

It’s a different situation with Coke, however. This New York Times article analyzing Coca-Cola’s variable pricing idea suggests that we have an intuitive sense of what a Coke should cost, and that messing with that price violates our expectations. Varying its price with the heat makes the pricing seems cruelly arbitrary; it seems to send the message “your pain is my profit”. It sounds like the sort of thing a cartoon villain (or the Ferengi on Star Trek) would pull.

It’s one thing for Uber to use surge pricing for events like holidays or tourist season; these events are predictable, an increase in price seems fair, and it doesn’t look like crass opportunism. However, in an unpredictable event that brings the city to its knees and strands thousands of people in the rain, surge pricing looks like making money off people’s misery.

Some businesses took the opposite tack — my friend Sandy Kemsley wrote on Facebook that she was “so proud to live in a city where last night, with 1000’s of stranded commuters, at least two hotel chains offered discounts”. It’s a financial risk, but I think it would’ve paid off. It would’ve been better for Uber to lower their prices during the storm and provide greater incentive for drivers to get out there and pick people up and treat it as a marketing expense rather than use surge pricing. However, I don’t think that will happen; if a serious disaster like Hurricane Sandy didn’t convince them, a far less serious problem like Monday’s storm has no chance of doing so.