Because this is an article about business, and because I grew up in the 1980s, in the era of They Live, I had to include this pic.

The “Yes, I work for a living” Prologue

Because this is an article in which I criticize business culture, and to head off any cries of “Socialist!” hurled at me, here’s the obligatory “Yes, I am a businessman, in a real job, and I actually do work for a living” statement:

Yes, I am a businessman, in a real job, and I actually do work for a living.

You can go look at my resume — it’s my LinkedIn profile. It’s no ordinary profile, either; it’s noteworthy enough to have been in the top 1% most viewed last year:

And not only do I work — I can work in all sorts of places. There’s my rather nicely set-up home office:

I also set up shop at client offices, such as this one in Calgary:

As regular readers of this blog know, I even get work done in places like Tampa International Airport, as this photo from a recent post of mine shows:

And now, the main topic of this article.

The Tweet

Recently, a Business Insider piece by Henry Blodget suggested that McDonald’s could still be profitable by increasing their wages, not increasing their prices, and accepting lower profits (according to Blodget, operating profit would be reduced to a “mere” $5.5 billion). Blodget’s back-of-the-envelope math was based on some erroneous assumptions (for starters, McDonald’s spending on employees accounts for about 24% of its revenue, not 17%), and face it, nobody’s going to buy into the idea of reducing profit for the sake of paying employees more — at least the rank-and-file ones, anyways.

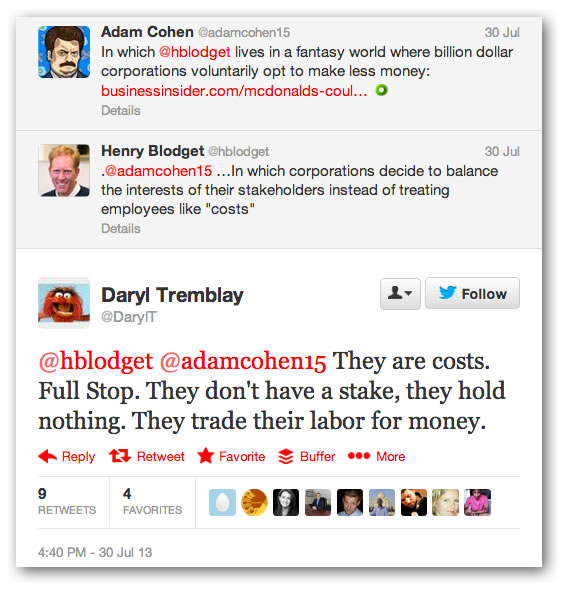

The article brought about a Twitter discussion that elicited a tweet from fellow IT consultant Daryl Tremblay that pretty sums up what the so-called “job creators” really think about job creation. Blodget made the radical (in some circles) suggestion that employees shouldn’t be treated like costs, and that’s when Tremblay chimed in:

Employees, Tremblay said in the tweet — and has been saying over and over again in subsequent tweets — “are costs. They don’t have a stake, they hold nothing. They trade their labor for money.”

If You’re Not an Owner, You’re a Cost

If you’ve ever taken an accounting course (I did, and at one of Canada’s best business schools t00; I figured that a technologist should know how to speak and relate to “the suits”), you probably know that on a balance sheet, this is correct. Your office building, equipment, furniture, and trademarks? They’re assets, that by virtue of being sellable, contribute money to the business. The people who come to your office building, use the equipment, sit in those chairs and do the work that make the company go? They’re liabilities.

Once again, if you took accounting, you know that I haven’t mentioned the final piece of the A = L + OE equation. A is “assets”, L is “liabilities”, and OE is owner’s equity. The equation says that once you take away the costs from the total value of the business, what you have left belongs to the owners. Included among the owners are shareholders.

The problem is that shareholders these days seem to think of the companies they invest in merely as “black boxes” that they put money into and magically have it multiplied. They’s not particularly interested in what the company does, or whether it even survives; only that it makes them rich without effort. This has led to the thinking that the best thing you can do for the company is maximize shareholder value — something described in Forbes as “the dumbest idea in the world”.This in turn, leads to:

- Installing — and gladly paying for — executive teams who believe that maxing out shareholder value is job 1. Unsurprisingly, companies focused on maximizing shareholder value tend to maximize executive salaries.

- Cost-cutting, and guess which costs are getting cut:

Eek! a cost! Cut it! CUT IT!

Creative Commons photo by “G.e.o.r.g.e.”. Click to see the original.

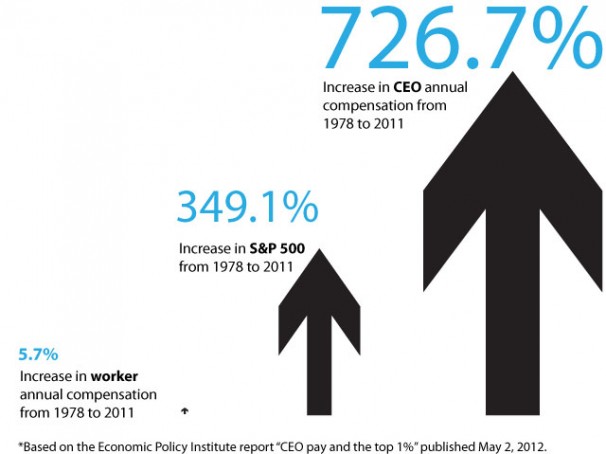

It turns out that the best possible investment you can make is to become the CEO of a publicly-traded company. It’s more than twice as good as simply having an S&P 500 portfolio and 127 times better than being a “cost”:

Graph from the Washington Post. Click to see the original.

A Little Real-World Example from Microsoft

Me in October 2010 at Microsoft Canada’s offices in Mississauga beside a giant Windows Phone 7 phone.

Back when I was a developer evangelist for Microsoft, I was one of the Windows Phone Champs, a hand-picked two or three dozen people from Microsoft’s worldwide ranks charged with getting developers interested in making apps for Microsoft’s then-new mobile phone. It wouldn’t be an easy job, as three years had passed since the introduction of the iPhone (and Steve Ballmer’s now-infamous dismissal of it):

Just before the launch, those of us in the Canadian arm of the company received an email from the then-CEO of Microsoft Canada, who said he was counting on our efforts. While it was implied that he wanted Windows Phone 7 Series (as it was called at the time) to make a big splash, and to get developers interested in building apps for it, and help the phone become a big success, that’s not what he wrote.

Instead, he specifically wrote that he wanted Microsoft share prices to go up as a result of Windows Phone’s introduction.

The Results

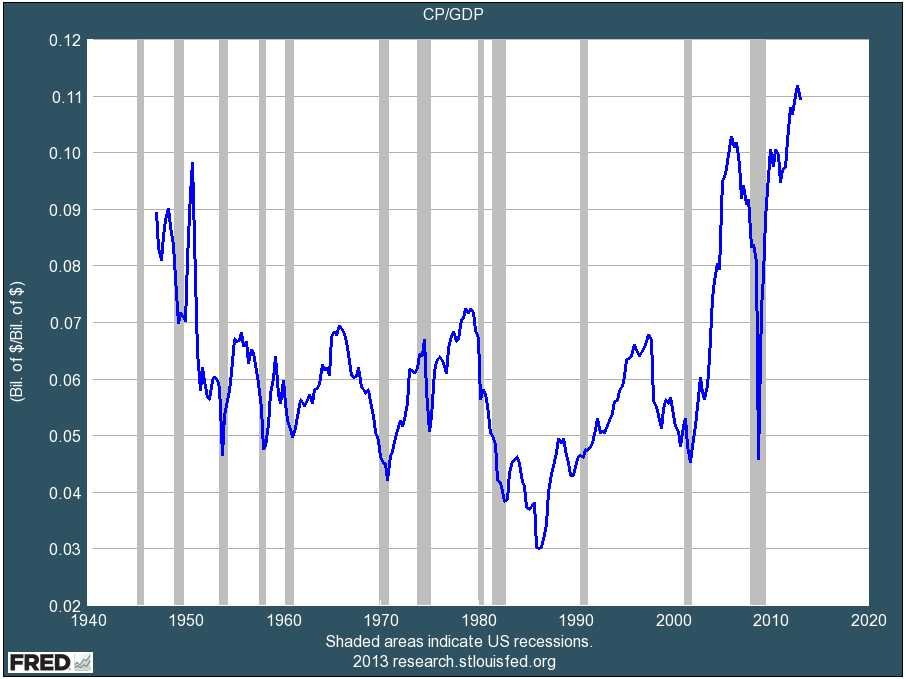

So while corporate profits and profit margins are way, way up:

Graph from Business Insider: Why Economic Growth is So Slow in 2013.

…wages, expressed as a fraction of the GDP, are way, way down…

Graph from Business Insider: Why Economic Growth is So Slow in 2013.

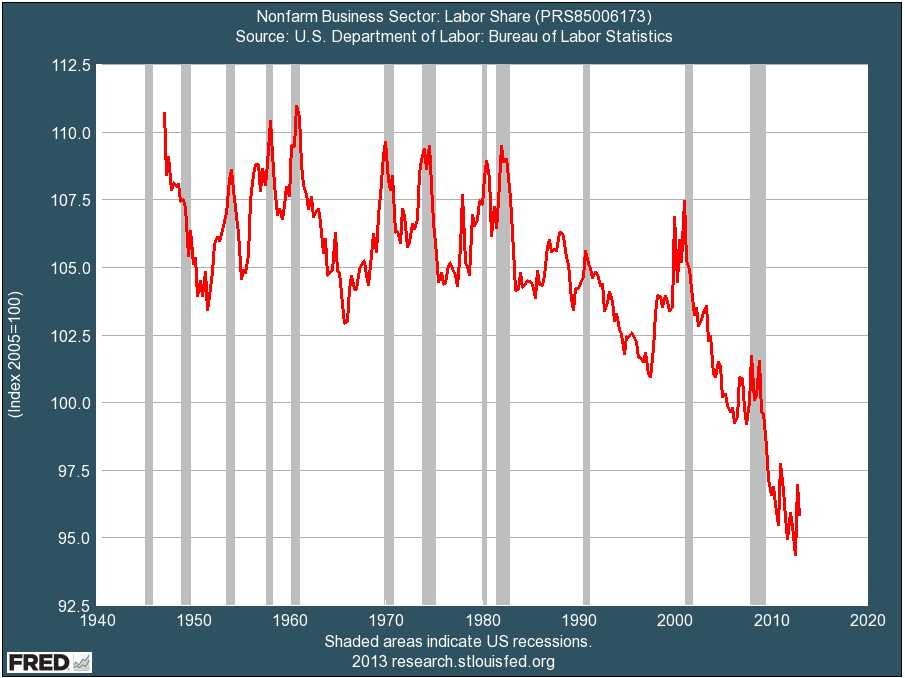

…labour’s slice of the corporate income pie is at its nadir, what with most of it going to owners and execs…

Graph from Business Insider: Why Economic Growth is So Slow in 2013.

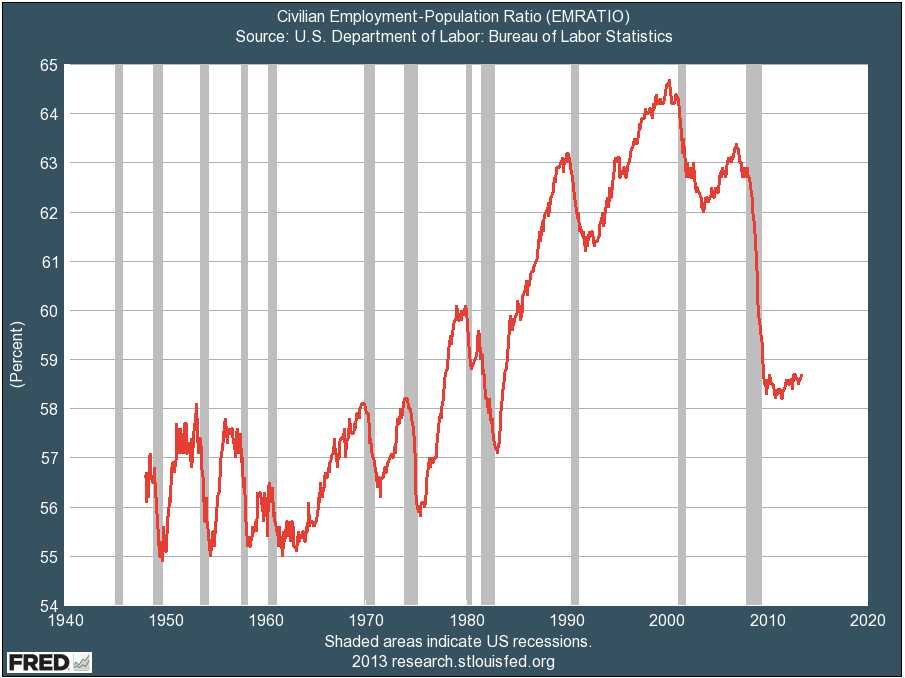

…and employment is the lowest it’s been since around the end of the Carter administration. (Or, from a purely balance-sheet point of view, all those pesky “costs” and “input” have been cut. Nicely done!)

Graph from Business Insider: Why Economic Growth is So Slow in 2013.

For more, see Henry Blodget’s articles, This One Tweet Reveals What’s Wrong With American Business Culture And The Economy. and Why Economic Growth is So Slow in 2013.

What Now?

Given this reality, it may turn out that some of the best advice to follow comes from this unlikely place:

When I was a kid, both Cracked and MAD were paper magazines, and Cracked was often MAD’s lower-rent, not-as-good poor cousin. In their present-day online incarnations, Cracked is so much better than MAD.

One reason present-day Cracked is a worthwhile read is because every now and again, they publish an article with material that really should be covered in school. Perhaps not with Cracked’s sarcastic, adult-humour angle, but it should be covered anyways. One such article is David Wong’s 6 Harsh Truths That Will Make You a Better Person, and particularly truth number six:

The world only cares about what it can get from you.

If you don’t end up being a CEO or end up being able to live off being a shareholder, your best option in the short term is to take this harsh truth to heart and make sure that if you’re a cost, you’re one that people are willing to pay for.

In the long term, a good strategy would be to bring Peter Drucker’s mantra back to the business world: “There is only one valid definition of a business purpose: to create a customer.”

I’ll close with Alec Baldwin’s Oscar-winning scene from Glengarry Glenn Ross (a movie a cited in an earlier post of mine, New York City’s Most Entitled Food Truck Ex-Employee), as a reminder of what it’s like out there:

(This speech was merely a dress rehearsal for the much-publicized dressing-down he gave his kid in a phone message.)

The first hint about O’Connor’s feelings about his former job is how he describes it at the end of the first paragraph: “Grilled cheese: gamified”.

The first hint about O’Connor’s feelings about his former job is how he describes it at the end of the first paragraph: “Grilled cheese: gamified”.

In the article, appropriately titled

In the article, appropriately titled