The review and its withdrawal

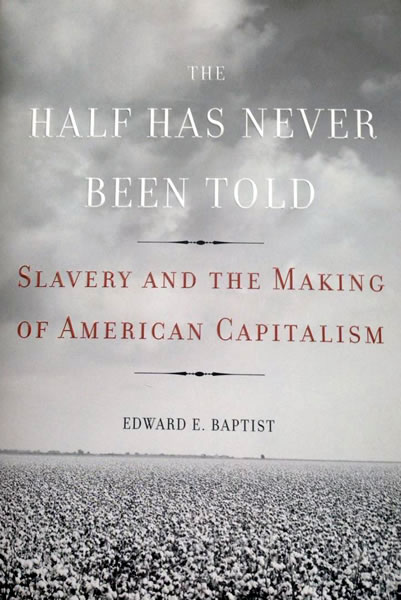

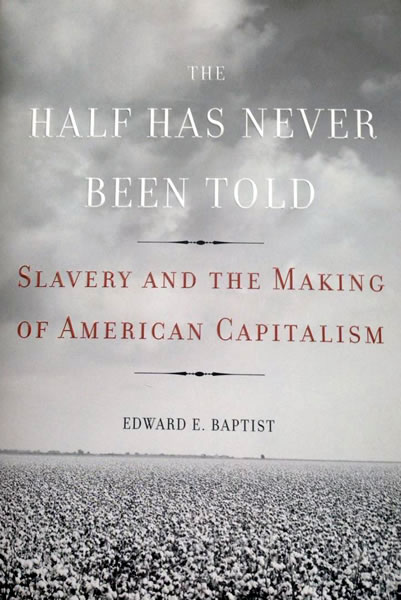

You can generally count on The Economist to provide an amusing, and sometimes educational read, even when they’re trying a little too hard to be glib and clever-clever in that Oxbridge upper class twit kind of way. However, there are exceptions to every situation, and such an exception reared its ugly head Thursday night online and in print in the September 6th edition. That’s when they published an uncredited review of Cornell history professor Edward Baptist’s book, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism.

Here’s a screen capture of this execrable article, complete with a photo of Lupita Nyong’o playing her role of “Patsey” from 12 Years a Slave — who was both a slave and a concubine to her white master — with the caption “Patsey was certainly a valuable property”:

The Economist’s anonymous reviewer or reviewers hated the book, their complaint being that it cast slave owners in a bad light. The two final paragraphs of their writeup serve as both a summary of their opinion and as an example of bigoted sophistry that will be cited in writing and ethics classes for decades to come:

Mr Baptist cites the testimony of a few slaves to support his view that these rises in productivity were achieved by pickers being driven to work ever harder by a system of “calibrated pain”. The complication here was noted by Hugh Thomas in 1997 in his definitive history, “The Slave Trade”; an historian cannot know whether these few spokesmen adequately speak for all.

Another unexamined factor may also have contributed to rises in productivity. Slaves were valuable property, and much harder and, thanks to the decline in supply from Africa, costlier to replace than, say, the Irish peasants that the iron-masters imported into south Wales in the 19th century. Slave owners surely had a vested interest in keeping their “hands” ever fitter and stronger to pick more cotton. Some of the rise in productivity could have come from better treatment. Unlike Mr Thomas, Mr Baptist has not written an objective history of slavery. Almost all the blacks in his book are victims, almost all the whites villains. This is not history; it is advocacy.

The article is bad enough in and of itself. At a time when America is still feeling the after-effects of its slaver history, from the continued activities of the Tea Party to Ferguson, publishing it is…well…

Needless to say, all their equivocating — which boils down to “Of course people who were treated as sub-human farm equipment because of the color of their skin were going to be biased against slavery!” and “Sure, they were whipped, but not so badly that they couldn’t produce higher cotton yields!” — led to complaints aplenty from the still-sizable non-Klan portion of the internet, and The Economist withdrew the review. To their credit and in “the interests of transparency”, they left the text online (but thankfully removed the photo of Patsey along with that terrible, terrible caption), along with doing some editorial distancing:

There has been widespread criticism of this, and rightly so. Slavery was an evil system, in which the great majority of victims were blacks, and the great majority of whites involved in slavery were willing participants and beneficiaries of that evil.

The #economistbookreviews hashtag is born

In the age of social media, you have more options than writing a letter to the editor (although I’d still recommend doing so, just to make sure that they get the message), and thanks to this fact, the #economistbookreviews hashtag was born. On Twitter, it accompanied imagined book reviews written with The Economist’s ruthlessly amoral sensibilities:

Some observations

These days, many people use the internet to inform their purchase decision-making, and it’s often the reviews that help tip the scales in the buy/don’t buy decision. If it was The Economists’ reviewers intent to kill the sales of this book for having the temerity to suggest some white people’s ancestors treated black people like beasts of burden, it’s likely backfired. The review has been covered in the Washington Post’s blog, Talking Points Memo, Slate (who give some advice, including the obvious “Don’t use movie stills in a review of a book about slavery”), The New Statesman, Poynter, Business Insider, and even Gawker.

History professor Will Mackintosh has an interesting explanation as to how the review survived editorial scrutiny, and why the visceral response to it seems to have taken them by surprise:

Here’s my theory: as a magazine, The Economist is perhaps the most articulate, erudite defender of the neoliberal capitalist order. They are too smart to waste their time as Laffer curve snake-oil salesmen or crude economic nationalist (cough cough, Wall Street Journal, cough cough), but nevertheless, the main commitment of their reporting and their commentary is to defend late modern global capitalism as an economic and moral good. Think Davos, not the Tea Party. And that’s why they don’t like Baptist’s book: it demonstrates unequivocally that modern capitalism was born in blood. Let me say that again: whatever else you might say about capitalism, it took on its characteristic modern forms of capital accumulation and labor “management” in the context of American slavery. For a group of journalists with a deep, almost unarticulated commitment to modern capitalism’s fundamental benevolence, this is an uncomfortable truth indeed.

Hence the critical review, and the particular nature of The Economist‘s criticisms. The book has to be wrong, because if it isn’t, then capitalism isn’t an inherently moral economic system. And it has to be wrong specifically in its description of how capitalism exploits labor. The review has to hold out hope that slavery provided incentives for slaveowners to treat their slaves better, that “the rise in productivity could have come from better treatment,” because otherwise, the book gets uncomfortably to the reality that modern capitalism gets its increases in productivity at the expense of its workers, too. That last point is pretty obvious to anyone who’s been paying attention since 2008 (well, and since the 1970s), but it’s one that The Economist’s ideological commitments can’t allow it to confront. And that’s why we got such an ugly and weird review of Baptist’s book … and why they withdrew it, with such apparent bewilderment.

A blogger going by the nom de plume of Pseudoerasmus Boukephalos, whose primary interests are “economic growth, history & development, plus the related issues of political and social modernisation” also read the article and took a tack removed from any of the moral issues involved. He decided to challenge the book’s thesis that it was the judicious and careful use of beatings that boosted the cotton yield:

The Economist‘s elf was lazily speculating, a priori, about what could have been the determinants of efficiency in southern cotton production. It’s possible the reviewer is familiar with some of the arguments and debates surrounding Time on the Cross, one of whose many controversial arguments was that slaves were becoming ever more valuable property in the antebellum American South and were therefore better treated than commonly supposed. But I doubt that literature is known to the reviewer, because then he would have been familiar with recent research on the sources of increased efficiency of cotton agriculture in 1800-60.

He produces charts that show a 2.3% annum growth in the cotton yield for 60 years straight and argues that you can’t get this kind of boost except through technological innovation. Improvements in cotton harvesting tools along with the introduction of new strains of cotton plant that produced more white fluffy stuff and were taller, and thus easier to pick.

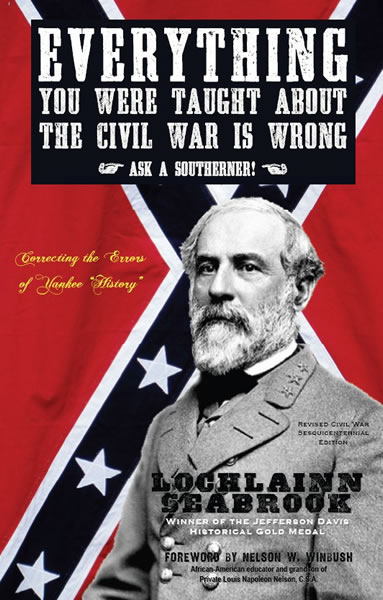

Not a parody, but an actual book. Click to see its Amazon page.

If you’ve read this far, go and read this essay: In Defense of Revisionism. Here’s an excerpt:

There was a time, for example, when historians didn’t worry much about the slave trade and the emergence of an economy based on forced labor. Historians likened the plantation to a “school,” and emancipated people as children let out of class too soon. Only slightly more than a half-century ago, historians began to “revise” that narrative, examining sources previously ignored or unseen, informed by new ideas about race and human agency. More recently, scholars have revised 19th-century images of the “vanishing Indian,” a wildly inaccurate narrative that lives on in public monuments and popular lore, and has implications for public policy.

This essential process of reconsideration and re-evaluation takes place in all disciplines; imagine a diagnosis from a physician who does not read “revisionist” medical research.

Revisionism is necessary — and it generates controversy, especially when new scholarship finds its way into classrooms…

In the same Economist issue as the review is an article on internship which has the subtitle “Temporary, unregulated and often unpaid, the internship has become the route to professional work”. I sense a pattern here.

Thankfully, none of their writers have used this to back a retort along the lines of “See? We know what toiling without a wage is like!”

We shouldn’t let The Economist off the hook so easily, but we should also remember the times when they do listen to the better angels of their nature (and yes, despite my foreign, non-American schooling, I know that’s a Lincoln quote). Last year, in honor of the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, they published an essay that was considerably higher-minded, and which ended with this paragraph:

America’s shameful past is fading. Skin colour is nothing like the barrier it once was. But the “pursuit of happiness” to which King referred is never easy, and never ends.

There’s more in a follow-up article.