Meeting Daniel Pink and hearing about his new book, “When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing”, at Tampa’s Oxford Exchange

On Friday, February 2nd at Oxford Exchange — a fantastic combination of bookstore, shop, restaurant, coworking space, design studio, and event venue in downtown Tampa — author Daniel Pink gave a presentation as part of the promotional tour for his new book, When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing.

I’m an avid reader of books on the topic of maximizing life, so Daniel Pink’s books hold a special appeal for me. I’ve enjoyed his books, from A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future to Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us to my favorite manga career guide, The Adventures of Johnny Bunko: The Last Career Guide You’ll Ever Need, a book that I’ve given away to more recent graduates than any other. Many goodies in my bag of tricks come straight from the pages of his works.

The presentation took place upstairs, in Oxford Exchange’s Commerce Club, a space with many beautiful rooms, including a large conference space where the Friday breakfast salon series of talks called Café con Tampa takes place. If you live in Tampa Bay and want to hear and meet the area’s big thinkers and movers and shakers, you should attend.

Pink opened his talk by dealing with the elephant in the room: the scar on his forehead, which gave him a very Harry Potter-like appearance. He said that he wished that there was an interesting story behind the scar, but it was simply the product of slipping in the shower. The bad news was that the result was ten stitches in his forehead. The good news — and the reason why would soon become clear — was that it happened in the morning.

“We lead lives that are series of episodes,” Pink said at the start of his talk. “Episodes by their nature have beginnings, endings, and midpoints. Each of these has a different effect on our behavior.”

His talk, like his new book, was about the oft-overlooked importance of when we do things. Among the questions he would answer, either at the talk or in his book, were:

- When should you exercise — early in the day, or late?

- Why should you never go to the hospital or schedule an important doctor’s appointment in the afternoon?

- Why does beginning your career in a recession depress your wages 20 years later?

- Why do both human beings and great apes experience a slump in midlife?

- Why is singing in a choir good for you?

- When during the year is your spouse most likely to file for divorce? “One of them is next month,” quipped Pink. “Check your email.”

“When we talk about units of time — things like seconds, and minutes, and weeks — you realize that most of them are completely made up,” he said. “They’re not natural in any sense; they’re things that human beings have created to corral time. But there are unit of time that are natural, like the day…and that has a big effect on us.”

With that, he introduced his thesis: that during the day, we experience a pattern that in turn affects the way we feel and how we perform.

He talked about a Cornell study using software called LIWC — Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count — to analyze 500 million tweets (“None of them written by the President,” he joked) for emotional content. The researchers of the study wanted to find out how emotional content varied through the day. This kind of study is called sentiment analysis, and in performing it on a large corpus of tweets, they found a pattern:

- In the early part of the day, they saw that “positive mood” has a peak.

- In the middle of the day, around the early afternoon, that general mood entered a trough.

- And finally, as the afternoon wore on, positive mood rose again, in a recovery.

He then pointed to Princeton researcher Daniel Kahneman’s “Day Reconstruction Method”, in which he gave people diaries to track what they were doing and how they were feeling for every hour they were awake. Its purpose was to determine what activities made people feel better or worse (commuting was the daily activity that makes people feel the worst), but it also gave them a look into whether time of day affected “net good mood” — and according to their data, it does. “Net good mood”, it turns out, experiences a peak in the morning, a trough in the afternoon, and recovery in the evening.

This peak-trough-recovery pattern occurs in many places, and while the pattern is hidden to many people, its effects are decidedly not.

He then went to a different topic: standardized testing in Denmark. Danish students take these tests on computers, but the students outnumbering computers, they had to schedule students to take the tests at different times of the day. When they mapped performance against time of day, they found something interesting, which they summarized as follows: a general trend that the later a student took the test, the worse they performed. In fact, the effect was pronounced enough that it was written up like so:

“For every hour later in the day, scores decrease… We find that an hour later in the day causes a deterioration in test score that is equivalent to slightly lower household income, less parental education, and missing two weeks of school.”

Given that policy and decisions about a student’s future can hinge on a standardized test, the edge or setback created by when the test is taken could make a big difference.

He cited some scary medical peak-trough patterns:

- Anesthesia errors: 4 times more likely at 3 p.m. than 9 a.m.

- Hand-washing in hospitals: Drops as the day goes on.

- In colonoscopies, they find half as many polyps in afternoon exams as in morning exams.

- Doctors are more likely to prescribe unnecessary antibiotics in the afternoon than in the morning.

“We’re very intentional about what we do — anyone here have a to-do list? We’re intentional about who we do things with — that’s why we have HR departments. We’re intentional about how we do things. But when it comes to when, we’re kind of loosey-goosey about it.”

This is a shame, because the difference in our performance between the time of day when we’re at our peak and when we’re at our worst can be just like getting legally drunk.

One way to help mitigate the effects of time of day on how we perform is to determine your chronotype, which is a fancy way of whether you’re a morning person, or a night owl. It’s simple to do: make a note of the time you go to sleep on “free days” (that is, a day when you don’t have to go to work the next morning) and when you wake up, and calculate the midpoint between those two times.

- If the midpoint is before 3:30 a.m., you’re a Lark or morning person. 15% of people are Larks, and a disproportionate educators are Larks.

- If it’s after 5:30 a.m., you’re an Owl or night person. 20% of people are Owls.

- It it’s between 3:30 a.m. and 5:30 a.m., you’re a Third Bird — something in-between.

If you’re a Lark or Third Bird, you follow the pattern of peaking in the morning, trough in the early afternoon, and a late afternoon recovery. Owls go through the pattern, but in reverse: they have the recovery in the morning, a trough in the late afternoon, and a peak in the evening.

Whether you’re a Lark, Owl, or Third Bird, you should adjust what you do to match the peak-trough-recovery pattern:

- During the peak, you should do analytic work.

- When in the trough, do rote, mechanical work: administrative tasks and other things that can be done “on autopilot”.

- The recovery period is one where your analytical powers are improved, and your mind is more flexible, which is great for insight tasks.

To prove the bit about the recovery phase and insight tasks, Pink presented the audience with a couple of brain-teasers which the majority of people get wrong. I’d seen the first one before — it’s “The Linda Problem”:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?:

a) Linda is a bank teller.

b) Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

(The answer is a; case b is a subset of case a, and therefore can’t be more probable.)

He then presented another one, which I’d never heard before:

Ernesto is a dealer in antique coins. One day, someone brings in a beautiful bronze coin. The coin has an emperor’s head on one side and the date 544 BC stamped on the other. Ernesto examines the coin, and instead of buying it, calls the police instead. Why?

I find that I do my most clever, creative programming in the evening, because that’s my recovery period, and as this audio recording from that part of Pink’s talk will show you, it’s my insight time:

It’s not every day that you get to impress one of your favorite authors.

Since attending the talk, I’ve been giving more thought to the way I arrange my day. I’m taking Pink’s advice to change my schedule so that I’m taking on tasks that require analysis and vigilance during the morning, “turnkey” work in the early afternoon, and saving my creative and learning tasks for the late afternoon and evening, when the elevated mood but lower vigilance lend themselves well to that sort of thing.

I’m also going to put more thought into when and how I take my breaks, as we tend to underestimate their restorative power.

Click the photo to see it at full size.

He showed a graph based on a study of Israeli parole boards, which showed that judges were more lenient after taking a break, and grew less lenient as time wore on.

According to Pink, the science of breaks is where the science of sleep was 15 years ago. Back then, the value of sleep was being introduced in popular culture, and the same is now happening for taking a break. The data shows that we should take more breaks, and we should take certain kinds of breaks. The idea of “powering through” and not taking a break is as bad as sleeping less to get more done.

Here’s what’s known about taking the right kind of breaks:

- Something beats nothing. Even a micro-break of a minute or two is better than no break at all.

- A break where you’re moving around is better than one where you’re stationary.

- Social beats solo. Breaks taken with people of our choice are more restorative.

- Outside beats inside. Nature has powerful restorative effects.

- Fully-detached — not talking about work — beats semi-detached.

Taking breaks — and especially the right kinds of breaks — can help mitigate the effects of the trough.

Pink then went into the Q&A session, where we learned a few things:

- The idea that amateurs take breaks and professionals don’t is completely backwards — it’s the other way around.

- During adolescence, our chronotype shifts towards “Owl”, which is why many high schools are now wisely scheduling the school day to start later.

- A couple with twin boys — one who’s a Lark, and one’s an Owl — were concerned about their Owl son’s performance on the upcoming SAT. Pink suggested that they could mitigate the morning’s effects on the Owl son by encouraging him to take a walk before the test, preferably with a friend.

- CBRE, a real estate company in Toronto, has a policy where you’re not allowed to have lunch at your desk, which is in keeping with the idea of fully-detached breaks being better.

- Having a brainstorming session? Don’t hold it in the early afternoon.

- There’s also something called the “Fresh Start Effect” — we’re more likely to stick with a change in behavior on “fresh start” days like a Monday, or the first day of the month or year, or on the day after your birthday rather than two days before your birthday.

- When people make decisions, they generally have a default decision. When being pitched to, this default decision is “no”. People are more likely to overcome the default during the peak, and immediately after a break.

- “This book has changed my behavior more than any other book I’ve written,” Pink said. “I became much more intentional about my own schedule… I take breaks in a way I wouldn’t have before — I always make a break list now.”

- On when to work: If you goals are to lose weight, boost your mood, or establish a habit, exercise in the morning. Exercise in the evening is better for avoiding injury, if you want it to be more enjoyable and less effortful, or if you want to break records (a large number of which are broken between 4 and 7 p.m.).

We then went downstairs to Oxford Exchange’s bookstore section to get our copy autographed…

…during which time Anitra asked Pink for recommendations for books that he found interesting. He wrote these on a post-it:

- Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carolyn Dweck

- The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt

- Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success by Adam Grant

My coworker Justin Downey was unfamiliar with Pink’s work, but came along based on my recommendation and greatly enjoyed the talk. I think we have a new fan!

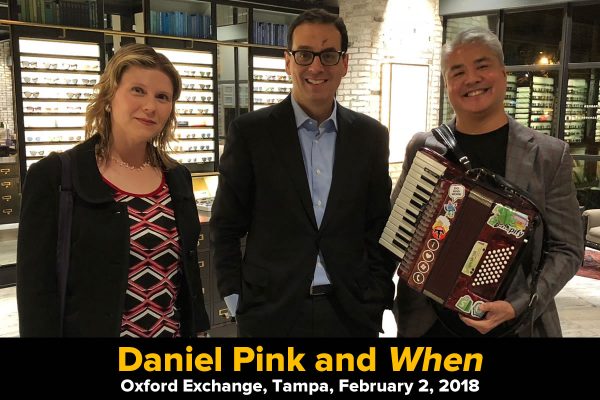

Of course, Anitra and I posed for a shot:

Recent Posts

A reminder for April Fools’ Day

Have a good April Fools’ Day tomorrow, but be mindful about your pranking.

How NOT to sell a computer

As I’ve written before, I sometimes browse Facebook Marketplace for nothing more than pure entertainment,…

Happy 10th anniversary, Anitra!

Ten years ago today, this happened: And since that day, it’s been an adventure. Thank…

Last Sunday’s accordion gig in Bonita Springs

It’s been over a year since I’ve played with Tom Hood’s band, the Tropical Sons.…

My plans for Burns Night 2025

Here’s the main course for dinner tonight... ...and that’s because it’s January 25th today, making…

View Comments