This article also appears in Global Nerdy. Like the previous article, it’s about my role at Microsoft and doesn’t delve too deeply into technology, so I thought it was suitable for a more general audience and decided to republish it here. Enjoy!

Mental Models and Bill Buxton’s “Draw a Computer” Exercise

In the mid 1990s, well before he was Microsoft’s user interface guru, Bill Buxton often asked people to carry out a simple little exercise: draw a picture of a computer. Most, if not all, of the people he asked would draw something that fit the common mental model of the desktop computer of the era: cathode ray tube-type monitor, keyboard, mouse and that box housing the motherboard and drives that many people mistakenly refer to as “the CPU”.

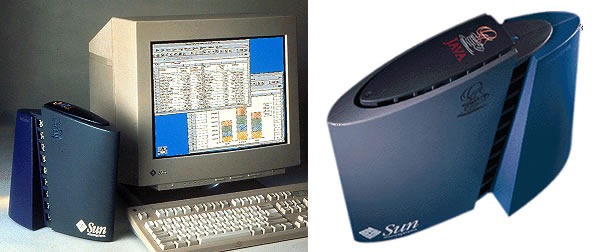

If Buxton were to ask the question today, the drawings of computers might look like these:

If he asked the question in the mid-to-late 1980s, the drawings might’ve looked like these:

![80s-era computers: Apple ][, Commodore 64, TRS-80 and IBM PC 80s-era computers: Apple ][, Commodore 64, TRS-80 and IBM PC](https://www.joeydevilla.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/80s-computers.jpg)

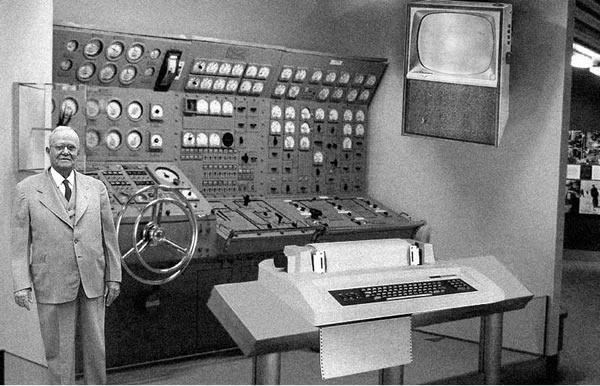

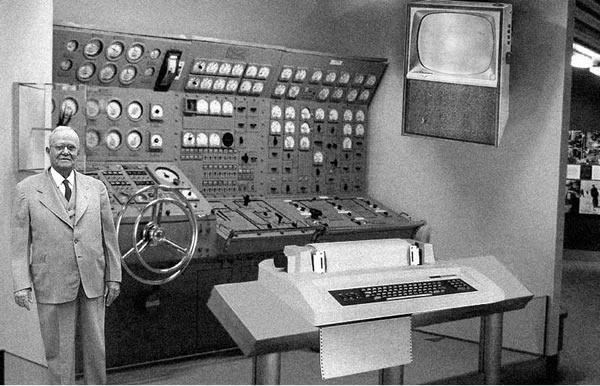

And had he asked the question in the mid-60s, the drawings might’ve looked like this:

Buxton likes to point out that the changes in computers from the 60s onwards are largely in the implementation technology, processing power and outward appearance. When most people draw computers, he said, they’re merely drawing their mental model, which is based on the outer packaging.

However, if you use the mental model of a technologist, computers have been essentially the same instruction/ALU/storage/input-output boxes whether they’ve occupied whole rooms or fit in your pocket. They’ve been pretty much the same at their core, in the same way that fancy tech and hybrid engine aside, there really isn’t too much that separates a present-day Toyota Prius from a Model T Ford.

If Bill Buxton could approach Microsoft Corporation as a person — and hey, that’s the way the law treats corporations, so why not? – and asked him/her to draw a computer, I suspect that s/he would draw something based on mental model of a souped-up circa 2000 computer: a desktop computer with a nice flatscreen monitor, running Windows XP and having a somewhat limited connection to the ‘net.

I think that this is a problem. I also think that the source of this problem is Microsoft’s success.

Microsoft’s Company Mantras

“A PC on every desk and in every home” was Microsoft’s longest-lived slogan and the company mantra for the first 24 years of existence. Like the best slogans, it succinctly summarized the company’s goal. The problem is that the goal has pretty much been reached. In most parts of the first world, a good chunk of the second world and even a sizeable fraction of the third world, you can easily find a desktop computer, and it’s quite likely that it’s running some sort of Microsoft software.

Since 1999, the company mantra – I really hesitate the use the phrase “vision statement” — has been a little more vague. The company’s been thrashing between them a little more frequently, as you can see in this list of mantras taken from chapter 1 of How We Test Software at Microsoft:

- 1975 – 1999: “A PC on every desk and in every home.”

- 1999 – 2002: “Empowering people through great software – any time, any place and on any device.”

- 2002 – 2008: “To enable people and businesses throughout the world to realize their full potential.”

- 2008 – present: “Create experiences that combine the magic of software with the power of internet services across the world of devices.”

The post-1999 mantra all seem a little limp in comparison to the original. Reading them, I cannot help but think of a quote attributed to web design guru Jeffrey Zeldman:

"…provide value added solutions" is not a mission. "Destroy All Monsters." That is a fucking mission statement.

Because the old mantra lasted for so long and the new mantras just don’t have the same straightforwardness and gravitas (How We test Sofware at Microsoft quotes Ballmer as saying that we may never again have a clear statement like the original to guide the company), the original remains quite firmly etched in the company culture and mindset.

I think it’s holding us back.

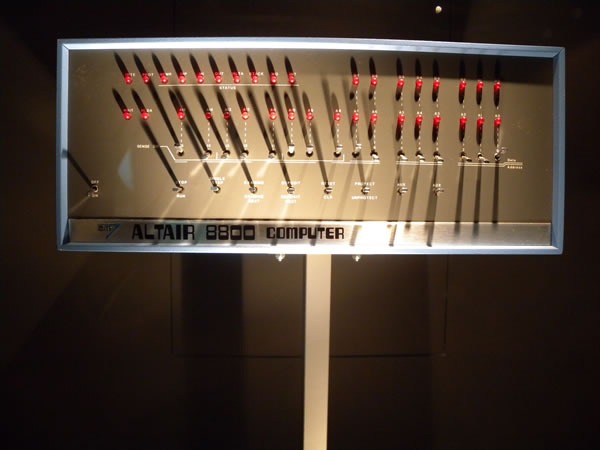

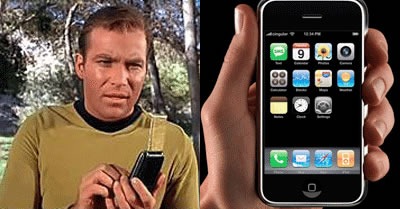

The Desktop as the Goose That Laid the Golden Egg

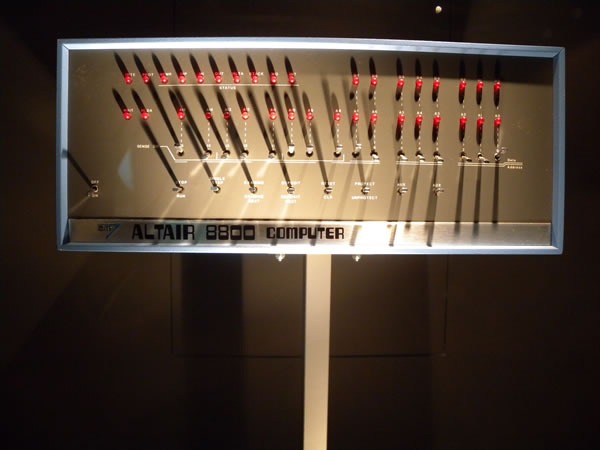

The original mantra doesn’t just focus on the desktop, it actually mentions it by name. In 1975, when computers were room-filling behemoths that you could access either via batch or time-share, the concept of a desktop computer was downright radical. If you think the iPhone is impressive (and yes, it is), imagine how mind-blowing the Altair 8800, the first commercially-available desktop computer, must have been to a geek back in the Bad Old Days. It was the platform on which Microsoft’s first product – a little programming language called Altair BASIC – was launched, and it was BASIC that in turn launched the company.

In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell talks about how the Altair 8800 was a golden opportunity for Bill Gates and his buddies at his fledgling company, then called “Micro-Soft”. Unlike a lot of other companies at the time, they took the desktop computer seriously. Even when IBM got into the desktop computer game in 1981, it was a product of their Entry-Level Systems division, a clear indication that they thought the PC was a machine you bought until you were ready to graduate to a real computer. I don’t think that this philosophy ended up serving them well.

Since the big boys were paying no mind to the desktop computer, upstarts like Microsoft had a big empty field in which to play, and they thrived. Crack open just about any late 70s/early 80s computer that had BASIC built in – even Apple machines — and you’ll see a row of ROM chips with a Microsoft copyright notice. It was Microsoft that swooped in with PC-DOS when a deal with Digital Research for a PC version of CP/M was slow in coming (and this is despite the fact that Gates recommended that IBM go to Digital for an OS). A lot of people’s experience with desktop computers (and Microsoft revenue) is defined by circa-1995 Microsoft thanks to Windows 95 and the results of Bill Gates’ memo titled The Internet Tidal Wave, both of whose influences are still felt to this day.

Once upon a time, it used to be unusual to walk into someone’s home or office and see a computer. These days, it’s unusual to walk into someone’s home or office and not see a computer, and Microsoft’s focus on the desktop had a lot to do with that.

The Desktop as Albatross

When electric motors first became available, engineers envisioned factories and eventually houses being equipped with a single electric motor. They imagined that the central motor would, through a series of gears and drive belts, be connected to whatever machines in the house or factory had to be driven by it. What happened in the end is that rather than relying on some central motor, electric motors “disappeared” into the devices that used them. Here’s an exercise to try: go and count the electric motors in your house or apartment right now. The number should be a couple dozen, and if you can’t find them, this article might help.

When big, room-filling computers first became available, engineers envisioned businesses being equipped with a single computer in a manner roughly analogous to the aforementioned big central motor. We know what happened in the end – while many businesses do make use of big datacenters, a lot of the computing power got spread out into desktop computers.

I have a theory that comes in two parts:

- Just as electrical motors disappeared into the devices that needed their work, and just as computing power got spread out from big mainframes into desktop machines, computing power is now both disappearing and spreading out into mobile devices and the web/cloud.

- Microsoft, with its desktop-centric approach, at least outwardly appears to be missing out on this migration of computing power.

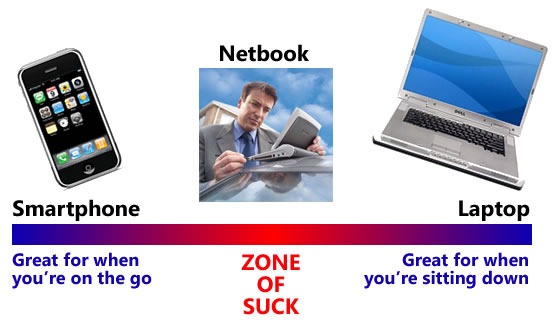

Most of the company’s attention, at least to an outside observer, seems to be focused on Windows 7. Yes, chances are that with computer sales being what they are, Windows 7 will probably end up on more of laptops and netbooks than desktops, but I consider those devices to simply be the desktop computer in a more portable form. It worries me that there have been more concrete announcements about Windows 7 on netbooks than upcoming versions of Windows Mobile, despite the iPhone and BlackBerry-driven evidence that the real mobile action is in smartphones.

(Tomorrow, I’ll post an article in which I argue that netbooks are a dangerous red herring pulling away our attention from devices like smartphones.)

Even when the company reaches out beyond desktop development, there’s no escaping the desktop “gravity well”. Consider ASP.NET (that is, the “traditional” ASP.NET, not the recently-released ASP.NET MVC). To my mind, as well as the minds of a lot of other web developers, it’s a web framework that tries really hard to pretend that the web doesn’t exist. It makes use of a whole lot of tomfoolery like ViewState to create a veneer of desktop app-like statefulness over the inherently stateless nature of the web and a programming model that tries to mimic the way you’d write a desktop application. It’s almost as if it were designed with the mantra “the web is like the desktop, but lamer” instead of “the web is like the desktop, but everywhere”. Although the framework works just fine and there are a number of great sites and web apps built on it, I think a lot of developers sensed this design philosophy and went elsewhere for web development.

(An aside: My old boss at OpenCola in late 2001 told me that he’d been meeting with Microsoft people and suspected that Internet Explorer 6 would be the final version of their browser. The expectation that web pages and web applications would be replaced by Windows client applications pushed over the net, a prediction similar to one made by the Java folks a few years prior.)

The same situation exists with Windows Mobile’s current user interface, which is basically a subset of Windows’ standard UI controls for the desktop, scaled down to fit smaller screens, and with a stylus standing in for the mouse. It’s almost as if it were designed with the mantra “mobile computing is like desktop computing, but lamer” instead of “mobile computing is like a mobile phone plus PDA and an MP3 player, but cooler.” If the ASP.NET design mantra is a whisper, the Windows Mobile mantra is a scream.

I suspect that the reason the XBox 360 didn’t fall into a similar kind of trap — “set-top boxes are like desktop computers, but lamer and only for games” – is that the XBox team is situated off the Microsoft Campus and less susceptible to the desktop influence.

My Mission

At my most recent one-on-one meeting with my manager John Oxley, we talked about a need for each member of our Evangelism team to define his or her area of focus. The Microsoft platform is a vast, nerdy expanse spanning the range from embedded computing all the way to Cray supercomputers; no single person can hope to cover it all.

He already had a good idea of what I wanted to focus on, and by now, I guess you do as well. I feel that just as computing expanded beyond the big computer rooms and onto our desktops, computing is expanding beyond our desktops into all sorts of different places:

- Invisibly, into the web and cloud in the form of web applications and services

- Visibly, into our pockets and living rooms, and embedded into all sorts of real-world things

While I believe that Windows 7 is a necessary part of the Microsoft platform, I’m not too worried about focusing on it – there are more than enough people at the company to promote and evangelize it. I want to focus on the platforms that I feel that Microsoft hasn’t given enough love and attention: the non-desktop platforms of the web, mobile and gaming, as well where they intersect.

It’s a big area to cover, but I think Microsoft needs to be active in this area if it wants to be true to its forward-looking roots. I even have a mantra for it: “To help web, mobile and game developers using Microsoft tools go from zero to awesome in 60 minutes.” I want to give developers both that rush when getting started with a new technology as well as the sustained passion to keep working with it, in the same way that Ruby on Rails and the iPhone got developers with an initial flash of excitement and turned it into long-term passion. It’s an ambitious, audacious mission, but no more so than the one coined by a bunch of scruffy nerds in New Mexico in the the 1970s: “A PC on every desk and in every home.”

Monarch Burger went to the trouble of making their apple pie look like a slice of homemade apple pie. While it seems appealing in its photo on the menu, it sets up a false expectation. It may look like a slice of homemade apple pie, but it certainly doesn’t taste like one. Naturally, it flopped. Fast-food restaurants are set up to be run not by trained chefs, but by a low-wage, low-skill, disinterested staff. As a result, their food preparation procedures are designed to run on little thinking and no passion. They’re not set up to create delicious homemade apple pies.

Monarch Burger went to the trouble of making their apple pie look like a slice of homemade apple pie. While it seems appealing in its photo on the menu, it sets up a false expectation. It may look like a slice of homemade apple pie, but it certainly doesn’t taste like one. Naturally, it flopped. Fast-food restaurants are set up to be run not by trained chefs, but by a low-wage, low-skill, disinterested staff. As a result, their food preparation procedures are designed to run on little thinking and no passion. They’re not set up to create delicious homemade apple pies.

![80s-era computers: Apple ][, Commodore 64, TRS-80 and IBM PC 80s-era computers: Apple ][, Commodore 64, TRS-80 and IBM PC](https://www.joeydevilla.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/80s-computers.jpg)