I saw this while going out for a neighborhood walk with Anitra this morning. I need to find out who the owners are, and make friends with them so th I too can cruise down the Hillsborough River in a unicorn boat!

I saw this while going out for a neighborhood walk with Anitra this morning. I need to find out who the owners are, and make friends with them so th I too can cruise down the Hillsborough River in a unicorn boat!

I saw this while going out for a neighborhood walk with Anitra this morning. I need to find out who the owners are, and make friends with them so th I too can cruise down the Hillsborough River in a unicorn boat!

I saw this while going out for a neighborhood walk with Anitra this morning. I need to find out who the owners are, and make friends with them so th I too can cruise down the Hillsborough River in a unicorn boat!

Since I’ve been avoiding the gym since March due to the coronavirus, a good chunk of my regular exercise has revolved around a 10K bike ride that I try to do at least five days a week.

Since I’ve been avoiding the gym since March due to the coronavirus, a good chunk of my regular exercise has revolved around a 10K bike ride that I try to do at least five days a week.

While Florida provides a fantastic climate for year-round cycling, Florida drivers provide a hostile environment for cyclists. The state is still number one in cycling deaths, and I have no intention of adding to that record. Luckily for me, my stomping grounds of Seminole Heights is a lovely residential neighborhood with plenty of quiet tree-lined streets with classic bungalows, “pocket parks”, gorgeous tropical foliage and other things to see that provide miles and miles of great cycling.

I take a different route every day, but at least half the time, I include Lake Roberta on that route.

The word “lake” is a little bit of a stretch — it’s actually a pond surrounded by a residential street, Roberta Circle:

Lake Roberta is home to all sorts of life forms, from the humans who live in the houses on Roberta Circle, to the creatures that live in or near the water. Those include an assortment of different kinds of ducks, a number of ill-tempered geese, ibises, turtles, lizards, squirrels, and possums. I don’t think that there’s a gator in there — with all the houses in the area, I can’t see the people who live nearby not calling wildlife control if they ever see one.

Roberta Circle provides a great way to help collect my 10K. By luck or design, each lap around the “lake” is a quarter mile, and the asphalt is nice and smooth. 4 laps around the lake adds an easy mile to my minimum goal of 6, and I get pretty scenery as a bonus.

My move from Toronto to Florida — a little over six years ago now — forced me to really apply a rule I try to follow: If you’ve been hanging onto something and never use it, let it go. Sell it, give it to someone who really needs it, or toss it. I’ve had to use this rule more since moving from Toronto to Tampa, as the move required me to take only what I could fit in my old car, and because I didn’t want to treat my mother’s basement in Toronto like a free storage place forever.

In spite of this rule, I’ve hung on to one piece of clothing that I’ve had since the very last days 1999 and that I almost never wear. It’s a grey zippered sweatshirt, a photo of which you’ll see later on in this article. There’s nothing terribly bad about it; I like the color, but the cut’s all wrong, it’s a little too big, it has ridiculous snap-straps all over (in the photo, you can see one of them around the neck). While it’s perfectly serviceable, I don’t like it enough to keep it under normal circumstances. It would’ve ended up at the drop-off of a Goodwill or some other charity ages ago. Still, I keep it, and I only get it dry-cleaned by professionals. Why? Because it’s a special gift from my dad.

In 1999, my former high school classmate André Fenton was doing neuroscience research at the Czech Academy of Sciences and decided that he wanted to ring in the year 2000 by throwing a big New Year’s Eve party in the nicest place that he could rent somewhere near Prague.

He found a great place — Zamek Roztěž (although these days, it’s marketed as Casa Serena Chateau and Gold Resort). It’s a “hunting castle” originally built in the late 1600s in the village of Roztěž, located in the Kutna Hora district, about 80 kilometers (50 miles) east of Prague. I was invited to the party, and while there, had a grand old time:

Upon hearing that I would be staying at a castle somewhere in the central European woods in the dead of winter, Dad decided to surprise me by buying me something to keep me warm. That thing was the zippered sweatshirt, and he gave it to me just as he dropped me off at the airport to catch my flight to Amsterdam, and then Prague.

“I got this for you. I don’t want you to be cold when you’re in that castle.”

I thanked him for the sweatshirt, gave him a big hug, wished him a happy new year in advance, and told him that I’d send photos that I’d take with my still-newish digital camera (1024 by 768 pixels in super-fine mode!) to mom via email (he never had an email address).

It’s not really what I would’ve bought, but it’s big and warm, I thought, and it served me well on the flight, in the castle (which wasn’t all that cold — they’d been doing a fair bit of renovating), and especially well on a hike around the castle grounds with some lovely company on the night of January 1st, 2000:

Because I am a big ol’ sentimental softie, not only have I kept this sweatshirt that I don’t really like all these years, but I take it with me whenever I travel far to someplace cold, as a sort of comforting tradition. I wore it walking through the streets of Prague, while shivering on the slopes at Whistler while trying to figure out how snowboarding worked. I wore it when I was conducting mobile technology assessments in the bitter cold of Athabasca’s oil sands. As I drove through the snow-covered hills of West Virginia on those chilly days of March 2014 as I moved to Tampa to be with Anitra, I had it on. I bring it with me on our trips to Toronto in winter. I last wore it during the handful of days that Tampa gets close to freezing, when the office’s heating just wasn’t keeping up. It keeps me warm, not only in the physical sense, but also in the way that it reminds me of his kindness and generosity.

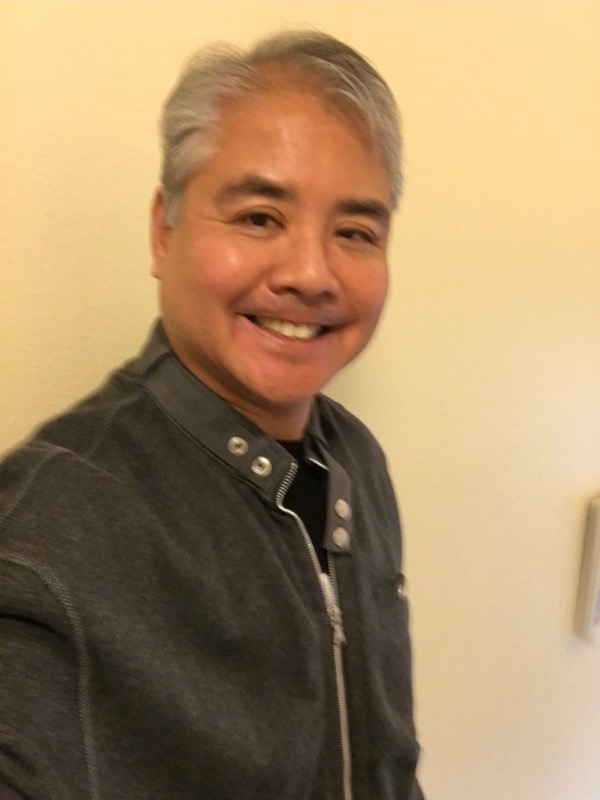

Me, in the “Dad sweatshirt”.

Dad died at the end of February 2006. But thanks to this sweatshirt that I normally wouldn’t be all that crazy about, I have a little bit of him that I can take with me when I’m cold and far from home. That’s why I’ll never part with it.

Happy Father’s Day, everyone.

On this day in 1967, the United States Supreme Court issued their ruling on the case of Loving v. Virginia, which struck down laws banning interracial marriage across the U.S..

The case involved Mildred Loving, a woman of color, who was married to Richard Loving, who was white. In 1958, they were sentenced to a year in prison for marrying each other, in violation of Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which made it a crime for people classified as white to marry people classified as colored. In court, they had to plead guilty to “cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth.”

The case also involved the state of Virginia, whose original state song lyrics included the line “There’s where I labored so hard for old Massa,” and the signature line of the chorus, “There’s where this old darkey’s heart am long’d to go.”

On this day in 1967, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Racial Integrity Act and similar laws were unconstitutional, and this ruling was also used as a precedent in Obergefell v. Hodges, the case that made same-sex marriage legal countrywide.

For some readers, 53 years ago may seem like pre-history, but think of it this way: Both presidential candidates were of legal voting age at the time. Actually, that does make it sound like pre-history. My point is that there are a lot of people alive today who were alive at that time (myself included, by a few months).

Today, we call June 12 Loving Day. While it’s victory for everyone, it’s especially so for me and Anitra, since it means we’re not committing a crime simply by being married.

Thank you, Mildred and Richard Loving, and Happy Loving Day, everyone!

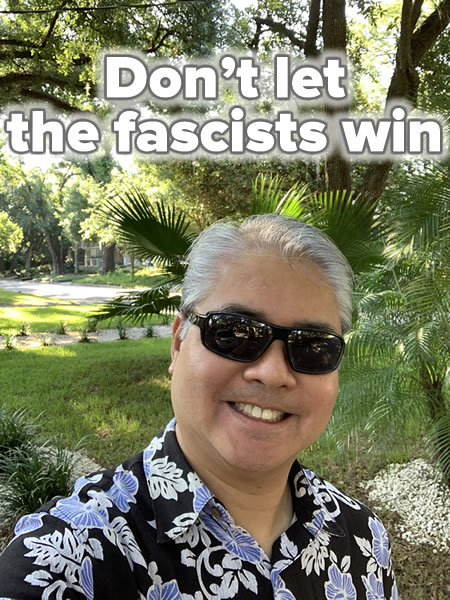

There’s an alt-right group who believe that a second Civil War — which they call the “boogaloo” — is coming, and they’re raring to take their part in it. The name “boogaloo” comes from the 1984 film Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, which was a sequel to Breakin’. The term “boogaloo” has since been contorted into similar-sounding shibboleths: “big igloo,” and quite notably, “big luau.” It’s the “big luau” expression that led to their adopting the aloha shirt as a signifier, along with camo pants, MAGA caps, and other clothing that’s meant to signify to their buddies that “I too am a fascist.”

That’s the point of this article…

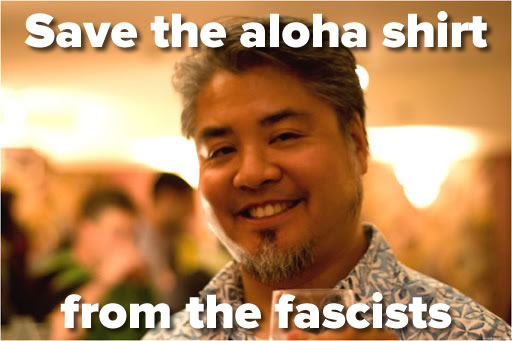

These alt-right assholes are trying to claim the Aloha shirt as part of their symbology, and I intend to do everything in my power to stop them. It’s bad enough that they’ve associated themselves with the tiki torch, but this Pacific Islander will not stand idly by as they attempt to co-opt my sartorial specialty.

Quite unsurprisingly, Aloha shirts are the creation of an Asian expats in Hawaii. One account credits its creation with the “Musa-Shiya The Shirtmaker” store…

…under the proprietorship of Koichiro Miyamoto, pictured below:

Another story says that Ellery Chun, a Chinese merchant who ran King-Smith Clothiers and Dry Goods in Waikiki. He is believed to have been the first to mass-produce pret-a-porter aloha shirts.

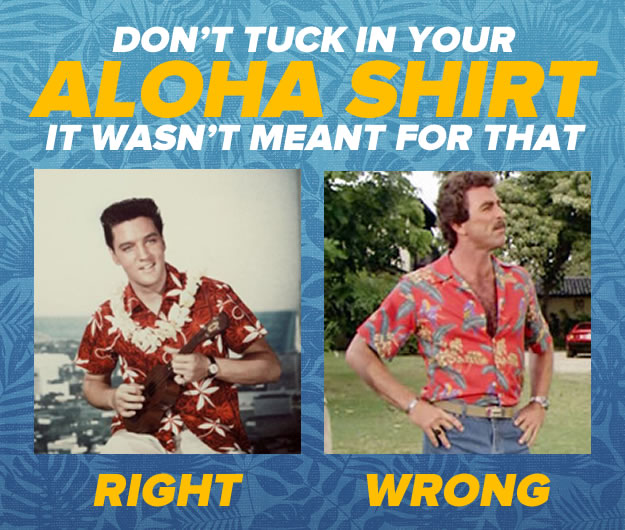

Because aloha shirts have straight lower hems, you’re supposed to wear them untucked, following the example of local Filipinos, who often wear dress shirts untucked (I do).

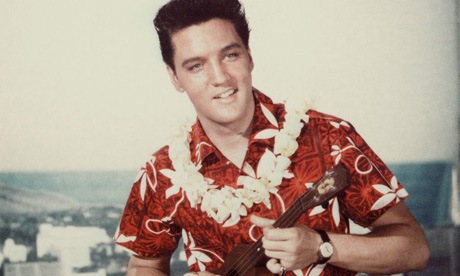

If there’s one person who should be credited with the popularity of the aloha shirt (the term “Hawaiian shirt” is technically incorrect), it’s textile manufacturer Alfred Shaheen. While he didn’t create the aloha shirt — they’d been made in Hawaii since the 1930s, and with the rise of air travel in the 1950s, tourists started them bringing them home from their vacations in the islands. Shaheen took these shirts, which were originally cheaply-made, and elevated them with better tailoring, materials, and patterns. The red aloha shirt that Elvis wore on the cover of the Blue Hawaii soundtrack album is a Shaheen design:

Those of you who’ve known me a while know that I maintain a fine collection of aloha shirts, and I’m often mistaken for Hawaiian. You have no idea how many times I’ve been greeted with “Mahalo!” It’s the perfect clothing for my general vibe, and it’s even more appropriate now that I live in Tampa’s sub-tropical climes:

The Wall Street Journal hit the nail on the head in their article Why the Extremist ‘Boogaloo Boys’ Wear Hawaiian Shirts with this paragraph:

…the inherent jolliness of a Hawaiian shirt gives heavily armed boogaloo boys a veneer of absurdity when they appear in public that can deflate criticism. “It’s tough to talk about the danger of guys showing up to rallies in Hawaiian shirts without sounding a little bit ridiculous,” said Howard Graves, senior research analyst at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala.

When an alt-right group has tried to appropriate something as a symbol, the brand has pushed back. After a neo-Nazi tried to declare New Balance “the official shows of white people” in 2016, New Balance quickly denounced white supremacy. Fred Perry has had to do the same because the Proud Boys are so fond of their shirts. Tiki Brand, the people behind the torches, have gone to great pains to distance themselves from the “very fine people” at Charlottesville. But since no single brand is associated with aloha shirts, there’s no organized pushback or single voice speaking out against the boogaloo bois and their sullying the aloha shirt by association.

There may be hope. Perhaps someone who’s a credible representative or symbol of Hawaii can speak out. The Honolulu Star-Advertiser made a good start in a recent editorial:

We’re Hawaii, and we want our shirts back.

Not only do we want them known by their proper name — aloha shirts, and not “Hawaiian shirts” as mainlanders call them — but in particular, they should not have been taken over by a violent political fringe group.

And yet, as a result of memes in social media, aloha shirts have been adopted as a kind of uniform for white nationalist groups. Folks who get the relaxed vibe of aloha shirts call that inappropriate. No aloha to those violent Hawaiian-shirt wearers.

Until we get that official voice, it’s up to us — those of us who wear aloha shirts out of love for the style, the signifier of being “the life of the party” or a person of good cheer, to celebrate a love or heritage of the Pacific islands, or any combination of all those — to defend our beloved items of clothing and keep the boogers from ruining them. Join me in this fight!

I’ll close with a gallery of Yours Truly in some of my favorite aloha and aloha-style shirts.

Tap the photo to see it at full size.

On Friday, I stopped by Produce Wagon, the fruit and veg stand that operates in our neighbourhood, just a few blocks away from the house on Tuesdays and Fridays. It’s always nice to see Patti and Fabiola, and was even better to find out that they’ve added an extra hour to their schedule — they’re now open at 13th and Crawford on Tuesdays and Fridays, from 9 a.m. to noon!

On Friday, I stopped by Produce Wagon, the fruit and veg stand that operates in our neighbourhood, just a few blocks away from the house on Tuesdays and Fridays. It’s always nice to see Patti and Fabiola, and was even better to find out that they’ve added an extra hour to their schedule — they’re now open at 13th and Crawford on Tuesdays and Fridays, from 9 a.m. to noon!

The vegetables I bought ended up in this morning’s scramble (pictured above), and will play a part in tonight’s dinner, which will be ma po tofu.

Seen on North Nebraska Avenue last weekend.

This one’s got all the major themes: Diabetes, unequal distribution, the profit motive, and “Oh jeez, I’m on my own; I’d better improvise something or I’m totally screwed.”