At the Doctor’s Office

Regular readers of this blog will remember the article last year in which I wrote about my overnight stay at the sleep lab at St. Joseph’s Health Centre. I got the results a while back, but it was only a couple of weeks ago that I saw my doctor about the results. (I’ll admit it. When it comes to matters medical, I’ve tended to put things off.)

“At one point, you were registering thirty-three apneas an hour,” said my doctor, pointing to my sleep lab results. “When that happens, you make this sound,” after which he made a sound at the back of this throat that sounded like a combination of snoring and choking.

“That…sounds bad.”

“That’s actually classified as severe,” he said.

“I thought that only happened if you were really overweight,” I said, “Say, in the weight class where you have to book two seats on a plane.”

“Well, losing weight can reduce apneas, but even if you’re at your ideal weight, you can still have it.”

One gag-a-riffic examination with a tongue depressor later, he said “You’ve got a narrow airway. That’s a big factor with sleep apnea.”

“So,” I said, “what are my options?” I was already dreading the answers.

“Weight loss will lessen your sleep apnea, but it won’t completely fix it.”

“I could stand to work out a little more,” I said, patting my gut.

“There are mouthpieces you can get, but they’re not always effective. There’s also surgery, which also isn’t effective — it’s basically scraping the inside of your airway, and it can actually make the other methods less effective.”

I already knew where this conversation was going.

“The most effective solution for you is…”

“CPAP?” I asked.

“CPAP,” he replied.

I must have grimaced at the thought of spending the remainder of my sleeping life hooked to a machine, because he said “You’ll be surprised at the difference it makes.”

CPAP

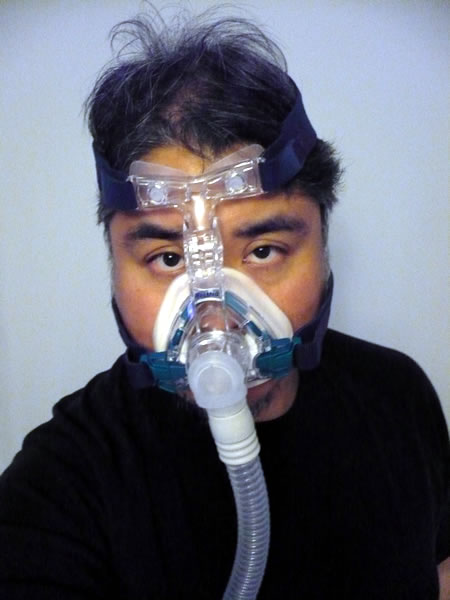

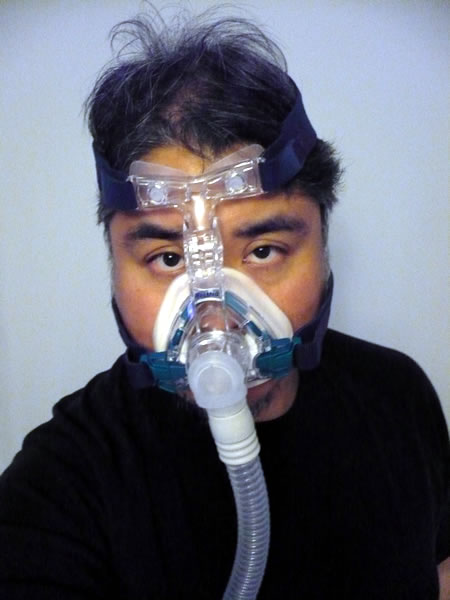

CPAP (pronounced “SEE-pap”) is an acronym for “Continuous Positive Airway Pressure” and is used to refer to the machine used by the man pictured below:

Sleep apnea is caused by the upper airway being closed off when the muscles relax during sleep. This cutting off the of the airway leads to a loss of oxygen, which triggers an automatic fight-or-flight response from the cardiovascular system and brain, which causes a waking response. This sort of thing, repeated over and over again, messes with your sleep and puts undue strain on the heart.

A CPAP machine provides pressurized air to the nose, which inflates the airway, keeping it continuously open. The end result is unobstructed breathing, which in turn eliminates sleep apnea and as an added bonus eliminates snoring.

The downside? You spend all night in something that looks like a gimp mask. (I’m aware that there are a number of people out there who do not see this as a downside.)

CPAP Shopping

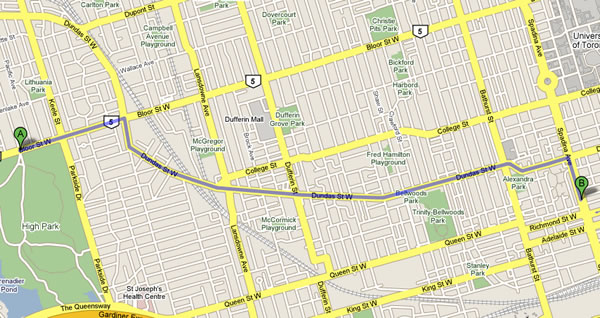

With a prescription and list of CPAP stores given to me by my doctor, I set out to do some CPAP machine shopping.

Lesson #1 of CPAP shopping: it’s not like shopping for a computer, DVD player or any other household or office appliance. You have to make an appointment since it takes about an hour and a half to get fitted, and here in Accordion City, it’s pretty much a Monday-to-Friday business.

The guy at the CPAP store was pretty nice and showed me a number of CPAP machines and masks, explaining the differences between them. As I looked over the different models, I thought that CPAP shopping might be a good way for techies like myself to understand what non-techies go through when shopping for computers and electronics.

I decided that the best strategy would be to go with the machine and mask combination that was the most comfortable. If it didn’t feel good, I figured, I wouldn’t use it regularly.

In the end, I chose the machine shown above: a Fisher and Paykel SleepStyle 604. It was squarely in the middle of price range and had the most comfortable-sounding features, including the best humidifier unit and a tube with a heated coil around it to prevent condensation. The more expensive unit, the ResMed (it’s the blue-and-white unit shown in the photo above with the man in bed) was smaller and looked nicer, but the store’s customers have reported that its humidifier wasn’t all that good.

Although the unit came with a mask, it was recommended that I pick out a mask that was a little more comfortable. The up-the-nose mask (like the one in the photo with the man in bed) obstructs your vision the least, but it wasn’t comfortable at all. I ended up going with the ResMed Mirage Activa pictured above because it felt flexible and comfortable. Although you can’t tell from this photo, the mask goes over the nose, not the mouth.

“Now for the fun part,” said the guy at the CPAP store. “Let’s hook you up.”

Bring out the gimp!

I was put in a reclining chair and strapped into my CPAP machine and mask. I felt like a muzzled dog.

“This will feel weird at first,” he said and the turned the machine on. A rush of air filled the mask. “Now breathe normally through your nose.”

I did, and despite the increased air pressure, it didn’t feel too weird.

“Now try breathing through your mouth or talking.”

As soon as I opened my mouth, it started venting a rush of air. It didn’t hurt, but it made me instinctively close my mouth.

“Yeah, that’s the pressurized air from the machine. When your mouth is closed, the air goes into your airway and holds it open. With your mouth open, it goes out your mouth and bypasses the airway. When that happens, your CPAP isn’t effective. So don’t open your mouth.”

“Not much chance of that,” I said. I should’ve just said “Okay,” because talking with the machine on is uncomfortable.

I walked out of the store with the machine and mask, carrying cases for both and a service plan (they service the machine, and also check its “odometer” to see that you’ve actually been using it). The total cost was about $1400, half of which will be covered by Ontario’s healthcare plan. I covered the other half on my credit card; the health coverage from work will reimburse me for that.

Back to the Sleep Lab

The next step: titration (pronounced “tie-TRAY-tion”, not “tit ration”). That’s the process where the appropriate amount of air pressure for the CPAP is determined, which requires someone to monitor you while you sleep.

This meant a return to the, the St. Joseph’s Health Centre Sleep Lab. Here’s the bed:

…and here’s the camera over the bed:

Here’s an interesting thing about the camera: the purple lights you see in the photo aren’t visible to the naked eye. They are visible through the LCD viewfinder of my digital camera. I assume that they’re ultraviolet and that the sensor in digital cameras has a wider range than human eyes.

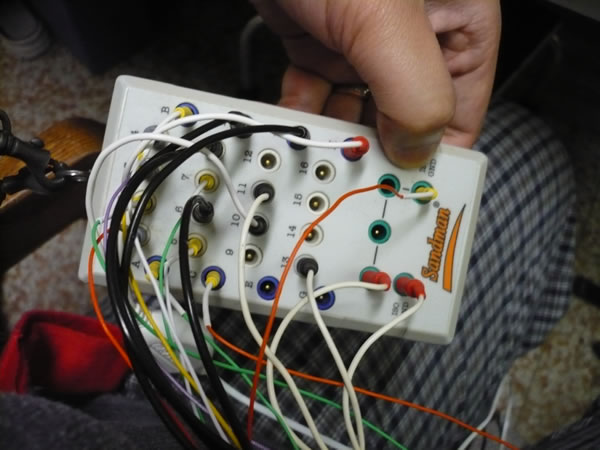

As with my last visit to the sleep lab, I got wired up with a lot of sensors:

- On my forehead

- Behind by ears

- On my head (which meant that I had hair full of electroconductive goop)

- On my neck (a piezoelectric sensor to detect snoring)

- A band across my chest

- A band across my stomach

- On my lower legs (to detect leg twitching)

- On my right index finger (heartbeat monitor)

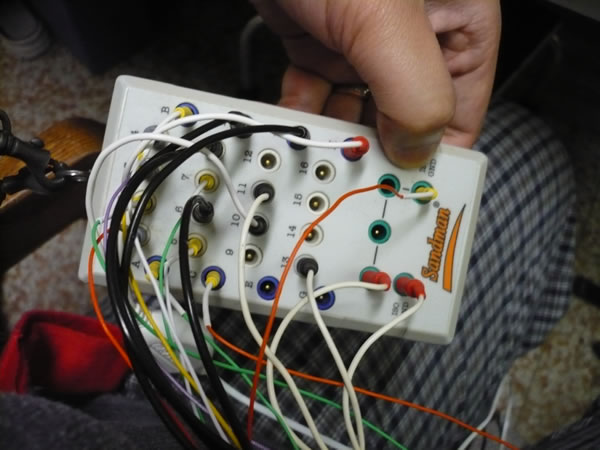

Here’s the box into which one end of the probes went:

…and here’s where the other end of the probes went:

Unlike my last visit, I had a little more trouble falling asleep. The throat mic was scratching my neck, and it took me a little time to get used to wearing a CPAP mask, air pressure and all. Near the beginning, my mouth would relax a couple of times, causing it to open slightly, which made me spit slightly in a zerbert-like way, which woke me up. I eventually got used to all these new sensations and drifted off…

Awake. Really, Really Awake.

…to be woken up at 6:30 a.m.. Under normal circumstances, a 6:30 a.m. wake-up after 6 hours of sleep would leave me groggy, but I felt quite alert. Under the circumstances, this was a very unusual feeling. I felt very well rested, as if I’d had 8 or 9 hours’ sleep.

I went home, showered and got dressed and went to work. I didn’t have my middle-of-the-afternoon lull where I’d need to get some caffeine or go for a walk to wake myself up and stayed very sharp through the whole day. “It’s like Flowers for Algernon! Well, the first part, anyway,” I said.

That night, I used the CPAP for the first time at home, and Wendy was very pleased at the silence. Aside from the very quiet sound of the CPAP (a gentle whoosh, much quieter than the fan on most computers) the room was silent. No snoring. If she can get used to looking over at my side of the bed and seeing me all “hosed up” — she calls me “The Hosebeast” now — we’ll be golden.

(Wendy would also like it if I would refrain from re-enacting Denis Hopper’s “nitrous oxide” scenes from Blue Velvet with my CPAP mask [not safe for work]. But I have to be me!)