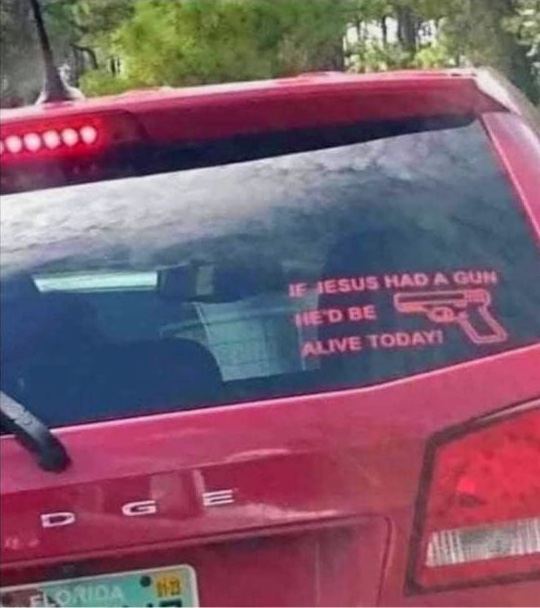

Alternate title: Tell me that you don’t know anything about Christianity without saying you don’t know anything about Christianity.

Pumpkin spice brake pads!

It’s the time of year when Ice Cold Air (in Seminole Heights, at the corner of Sligh and Central) puts out this seasonal promo.

It’s the time of year when Ice Cold Air (in Seminole Heights, at the corner of Sligh and Central) puts out this seasonal promo.

I am that dog

I try to do a 10-kilometer (6.2 miles) bike ride every day, but once a weekend, I take a mid-ride break at Spaddy’s Coffee, a coffee truck in my neighborhood of Seminole Heights with an outdoor seating area.

I try to do a 10-kilometer (6.2 miles) bike ride every day, but once a weekend, I take a mid-ride break at Spaddy’s Coffee, a coffee truck in my neighborhood of Seminole Heights with an outdoor seating area.

I’m enough of a regular that they can often remember my usual order: a “Heights Cold Brew,” which is their excellent cold brew mixed with condensed milk, in the style of Vietnamese coffee.

After all this time, I just noticed that they have something on their menu called “Espresso Lemonade,” which is what it sounds like: lemonade with a shot of espresso. I’ll have to try it the next time I go there.

This was a fun one: The Glazer Children’s Museum celebrated its 11th birthday with a big party at Curtis Hixon Park, located right by their front door in downtown Tampa. We’d already planned to attend when they suggested that I play some accordion numbers between acts on the big stage. I was honored by the request and was only too happy to play for a good party and a great cause!

Ever better, Captain Fear, mascot for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, joined me onstage! We had a grand old time.

I played:

- Baby One More Time (Britney Spears)

- What Do You Do with a Football Pirate

- Plush (Stone Temple Pilots)

- Should I Stay or Should I Go? (The Clash)